Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Making revelations and family connections. Genealogy, Family History, African American Family History

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

As I dig for my roots, I add another relative to my family tree: my second great-aunt, Malinda Method.

I gathered several documents, including her marriage registry, census records, death announcements, and death certificate, to develop a brief sketch of her life.

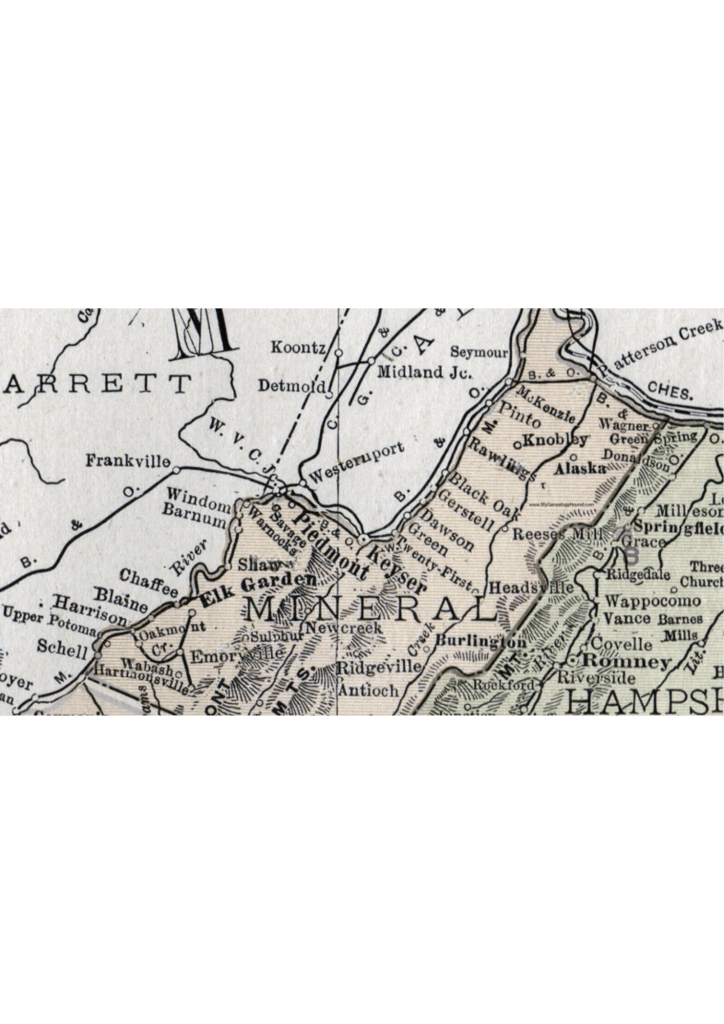

Malinda is the second-oldest of Solomon’s children. Recently, I learned about her passing in my hometown. The earliest document I have is her marriage registration in 1876. Matilda Methodist, 22 years old from Virginia, married James W. Galloway, 24 years old from Maryland, in Piedmont, West Virginia. The registry says her parents are unknown.

How do I know that this bride is my aunt if her parents are unknown and her last name is different?

According to Matilda/Malinda’s age at the time of the marriage registration, her birth year is 1854. West Virginia was not a state during this time. Emancipation liberated enslaved people in 1863, and West Virginia abolished slavery in 1865. Unfortunately, she was born in bondage. It is not unusual for formerly enslaved people to forget their parents’ names if they experienced separation.

Solomon married his wife, Mildred, in 1869. Antebellum laws prohibited enslaved people from legal marriages. Newly freed people experienced financial hardships, and a couple postponing to make a union legal is understandable due to registration fees.

Finally, the name Matilda may have been a clerical error by the registrar. All the supporting evidence recorded after her marriage indicates that her name is Malinda and that she is the daughter of Solomon Method.

The 1870 Federal census was the first to include African Americans counted by name, and Solomon’s family members are together except for Malinda in Moorefield, West Virginia.

| Solomon | 53 |

| Mildred | 52 |

| Amanda | 20 |

| Phebe | 16 |

| Charles Clinton | 12 |

| Mary Alice | 10 |

| Mary Jane | 6 |

Table 1: Abbreviated and Derived Table from the 1870 Federal Census.

James and Malinda Galloway thrived in Westernport, Maryland. Initially, he worked as a blacksmith. They owned their homes. Her husband retired as an engineer from the local Paper Mill located in Piedmont. The couple experienced child loss. Malinda became a widow in 1928 when James died two years after he retired. Therefore, Malinda lived alone. Most of her immediate family members had passed around this time as well.

| Method Family Vitals | |

| Mldred | 1818 – 1875 |

| Solomon | 1817 – 1881 |

| Amanda | 1850 – 1894 |

| Phebe | 1854 – 1930 |

| Charles Clinton | 1858 – 1933 |

| Mary Jane | 1860 – 1933 |

| Mary Alice | 1864 – 1900 |

Later in life, she regularly visited her grandnephew during the holidays in Columbus, Ohio.

Click the link to see how Malinda Galloway may have traveled to Columbus in 1941.

Charles Arthur Method was the grandson of Reverend Charles Clinton Method. In the 1920s, Charles Clinton became the assistant pastor of Mt. Vernon A.M.E., located in the historical Bronzeville community on Mt. Vernon Avenue in Columbus. Family members are still active in this church. Rev. Method’s son, Dr. William Arthur Method, co-founded the Alpha Hospital in the same area. Dr. Method died a few years after his father in 1936. William’s son, Charles Arthur, lived with his wife on the East side of Columbus, in Bronzeville. During Malinda’s visit in December of 1941, she passed on the 17th.

My grandmother migrated to Columbus in the later phase of the “Great American Migration” in the 1950s, following her older sisters, who relocated there in the 1940s. She became a member of Mt. Vernon A.M.E. I discovered our connection to the local historical figure, Dr. Method, years ago.

My cousins and I asked each other, Did they know about us?

Sources:

West Virginia Counties Marriage Registry

Federal Census records

Allegany County Voters’ Registration

Franklin County, Ohio Vital Records

Piedmont Herald Newspaper

Cumberland Times Newspaper

In this blog, I am sharing how my interest in family history began after watching the 1977’s T.V. series Roots by Alex Haley.

I was so inspired by Mr. Haley’s storytelling of his family’s history that my mom bought me an Ebony Jr., family research kit to build my family tree and a cassette tape recorder to record my family interviews.

I scheduled my first interview with my Great-grandpa Jarrett Ervin. Ervin is spelled E-R-V-I-N. I am pointing out this spelling because it has changed over the years. Great-Grandpa was in his 90s. He lived in Columbus, Ohio, with his oldest daughter Mary, who was my maternal Grandmother. Grandpa Ervin’s bedroom was at the end of the hall.

His room had an armoire, and not a closet.

He was a widower by seven years. His wife Great-grandma Sarah Grimsley Ervin passed in 1970.

I asked him my first question, “Grandpa Ervin, What was it like living in Alabama?”

As he opened his box of photos, he answered slavery. He handed me a picture of a woman standing in a field of cotton. He pointed that’s my sister.

I couldn’t focus on the photograph because his answer confused me.

Grandpa Ervin, you were not born in slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation was during the Civil War. I explained.

He repeated that it was slavery. Then he signaled for me to return his photo and proceeded to close his box, escorted me out of his room and shut the door.

I was a young, inexperienced ten year -old interviewer. Since my first interview, I understand to ask follow-up questions rather than to correct someone’s experience.

When Grandpa Ervin shut his door, he shut down my interest in family history too.

Recently, family history piqued my interest again. Ancestry.com has made researching easy. In their database is where I found them. I found Grandpa Ervin’s dad with his parents, his sister, his grandparents, and cousins by the dozens living together in the 1880 census. It was a great discovery.

I called my mom on the telephone. I described to her their beautiful names, Boston, Luke, Mariah, Julia, Moses, Prophet, and Shepherd. Another thing about their names, their surname was spelled I-r-w-i-n.

Today I will highlight my Cousin Shepherd. When I see the name Shepherd, I think of someone responsible, law-abiding, and brave.

According to the census records, Shepherd was born 1862. I smiled. I thought he did not have to pick cotton for free.

Shepherd and my great-great-grandfather Boston (Jarrett’s father) were first cousins. They were a year apart in age. I can imagine they were like brothers like their fathers Luke and Moses. Luke was Boston’s father and Moses, Shepherd’s.

The next document I would find for Shepherd would be a convict’s record. This find would be a shock to my soul.

Shepherd broke the law…

He was convicted of robbery on March 2, 1899, and sentenced for 25 years. He would have been 27 years old. The record does not fit my notion of someone with the name Shepherd. The file does not provide details of what was stolen. I doubt it valued 25 years of Shepherd’s life. My Great-grandpa Ervin was 12 years old during this time.

To paint a clearer picture of Shepherd’s conviction, I must go back to 1865 when the 13th amendment abolished slavery. The Southern states suffered financially due to the loss of free labor. As a result, Southerners concocted black codes and city ordinances to restrict the newly freed Americans’ freedoms. African Americans found themselves falsely accused of crimes and bogus violations. There were trials, but not trials judged by a jury of their peers, but all white male jurors.

As an Alabama inmate, Shepherd worked at Pratts Mills, a textile company – cotton. Alabama prisons had a practice of leasing their convicts. They arranged for prisoners to work for private companies or individual planters. These agreements covered the inmates’ food and housing.

Shepherd more than likely worked in the picker house to haul the boxes of cotton to be cleaned. Something I thought Shepherd would not have to experience picking cotton without pay. In my opinion, an incarcerated person working in a picker house hauling cotton is the same as an enslaved person working in the cotton field. It is forced labor without pay. We understand today that convict leasing is coined “slavery by another name.”

Even the great Confederate cavalry genius Nathan Bedford Forrest, his regiments eviscerated by four years of war, was swept aside with impunity. Wilson crushed the last functioning industrial complex of the Confederacy and left Alabama in a state of complete chaos.

Author Douglas A. Blackmon, “Slavery by Another Name.”

Many times in the convict leasing settings, these inmates were unsupervised. Arguments would become physical. No one in authority was there to stop any brawls. Sometimes these fights would end in death. I believe that was my cousin Shepherd’s fate. The record described his injuries as left eye out, scar over the eye, and a scar on lower left chin.

On December 22, 1900, another inmate took Shepherd’s life.

My Great-grandpa Ervin would have been 14 years old. Old enough to attend a funeral, old enough to listen to grown folks talk about what happened to Cousin Shepherd, and old enough to understand that after the North won the Civil War, President Lincoln proclaimed emancipation, and the 13th amendment abolished slavery, he lived in an oppressive state.

Great-grandpa Ervin described to me his Alabama experience correctly.

It was slavery.